On Friday, April 14, 2023, my wife and I drove to Waterloo (Ontario, Canada) to attend a unique public lecture, "The Jazz of Physics." The Perimeter Institute hosted an informal talk catering to the public interested in jazz and how physics impacts and contributes to improvisation based on the search for quintessential cosmological questions and answers. Coincidentally, the presentation was held on the very same day as the world concurrently celebrated "World Quantum Day."

The Perimeter Institute's (PI henceforth) primary goal is to train, teach and explore avenues concerning the fundamentals of scientific research in theoretical physics. In addition, its responsibility is to furnish the world with the next generation of physicists with the knowledge to change the future. Its secondary goal involves the global stimulation of interest in theoretical physics through educational outreach programs, podcasts and educating the general public (such as myself) about the wonders of the physical world that envelopes us. I'm proud that this Institution figuratively sits in my backyard, and I feel privileged that they care enough to invite me and the world to their front door.

Luminaries that have graced the halls of PI include the late Stephen Hawkings and renowned cosmologist Neil Turok, to name a few.

The PI is located on the traditional hosted lands of the indigenous Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, and Neutral peoples on the Haldimand Tract.

Cosmological Jazz Maestro

>.png) |

| Stephon Alexander |

And, now, The Jazz

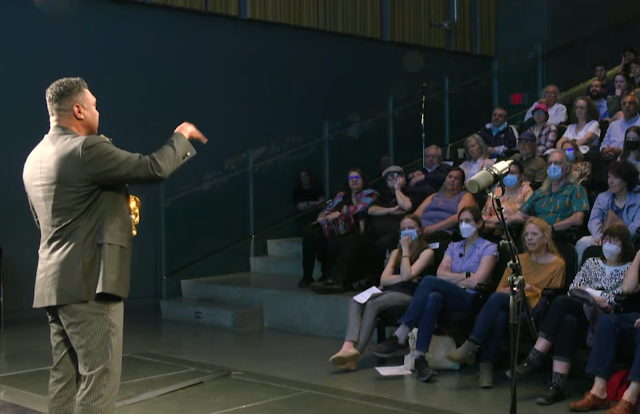

I have been a long-time, serious jazz fan since high school at age 15. However, most of the friends I hung with had no idea who Coltrane, Davis, Pass, Fuller, Parker or Dizzy were, and I'm sure they didn't care. When I did mention them, the looks I got were sure to convince me that they thought I had arrived from the same place Alexander correlates with jazz! To my young mind, jazz transcended the cosmos and had claimed as its birthplace, hence the use of jazz term: far out man. At 15, there was no association between jazz and the Universe, just the slang that came with the way-out coolness of the genre. To be in line with my friends, I also listened to popular mainstream music, but jazz ruled. Fast forward to my life in the cosmological time of nanoseconds; I still listen to and respect jazz and the men and women who create it, Stephon Alexander being a new, modern addition to the honour roll as both musician and educator. Many of us have studied physics for what it is: a study of the natural world to understand how things work at a fundamental level. It's the study of scales, from the very small to dimensions as large as the Universe. However, in Alexander's case, the word scale may be variable, suggesting vibrations to accommodate the notion that lends itself to sound, ergo musical rudiments: the heavenly gift of music, in this case, jazz. So, it came as no surprise when I received an email concerning a public forum about the melding of these two disciplines; we procured tickets for an evening of self-discovery in the interest of two subjects I love.The public lecture that Stephon Alexander delivered was dynamic, vibrant, and engaging. His breadth of knowledge of physics, history, and music is astounding, in-depth and delivered with exuberance; his charisma is infectious. The audience was highly receptive, comprised of what I could tell were musicians who thought they were physicists, physicists who believed they were musicians and some who thought they were both! (including me).

Post introductions, Alexander wastes no time bending our minds with his concepts, theories, and deductions peppering his talk with numerous examples guaranteed to stimulate and open your mind to an alternative way of approaching music, the Universe and the coupling of these two concepts to illustrate their most intimate connection: well done.

Alexander begins his lecture with what he describes as full disclosure, i.e., look at parallels between music with a focus on jazz music and cosmology and particle physics, with an emphasis on analogies not implying that everything that the talk encompasses in the Universe is jazz or that jazz is the Universe. Cleverly, he does not disclose his beliefs; the onus is a presentation for individual interpretation with some help from someone who delves deeply into both disciplines.

Alexander begins his lecture with what he describes as full disclosure, i.e., look at parallels between music with a focus on jazz music and cosmology and particle physics, with an emphasis on analogies not implying that everything that the talk encompasses in the Universe is jazz or that jazz is the Universe. Cleverly, he does not disclose his beliefs; the onus is a presentation for individual interpretation with some help from someone who delves deeply into both disciplines.

Let's Not Forget Why We're Here, The Physics

Alexander begins the journey into the science of sound and tonality with a historical perspective through the ages. He starts with some of his history and the influences that contributed to his current involvement in physics and music. Growing up reading, like many of us, comic books were a staple in his life; the fantastic stories of superheroes changed due to science's effect, making him fall in love with this discipline. However, he also grew up in a musical family where the expectation was that he would assume a musical/artistic life; this contributed to a conflict where to this day, he still believes exerts an arena of competition. As an audience, we are experiencing this aggression of conflict portrayed before our eyes his resolve: write about it and give public talks on the subject.

|

| Albert Einstein and Violin Photo source: unknown |

Next, Alexander takes us to the rudiments of musical understanding; to the Greeks, Pythagoras, to be exact. Alexander suggests that Pythagoras, having spent eight years in Egypt, had a sense of Western and African science. In combination, he believed in the music of the spheres, that the planets contributed a harmony in proportion to the distance from the Earth (Terracenteristic at the time). He created the term Cosmos referring to the order that ordained harmony in the Universe. To prove a theory, Pythogras created an instrument called the Monochord, a board with one string (hence mono) and an adjustable bridge to change the notes, therefore, pitch. In modern times, using the fingers achieves the same effect, demonstrated by using the upright bass by fellow musician Denis Rondeau.

|

| Monochord (Medieval Drawing) |

Pythogra's study of whole numbers led to his belief that these numbers are sacred. His study of the music of the spheres was what he believed was going on with the planets, and these numbers, in turn, led to ratios which contributed to our entire diatonic; all the scales we use today are based on what he did and what we know as the Western Tonal System.

Next on Alexander's list of contributors is Johannes Kepler, who trained in music theory. His way of thinking has evolved due to the new way of addressing the heliocentric system. For example, he computes the ratio of planet velocities as they move relative to the sun: in conclusion, the Earth resounds as a perfect 5th. Again, he parallels music and physics.

One must address wavelength to discuss music. When broken up, a wavelength exists as fractions; Alexander explains that a fifth of the fraction exists in music as a perfect fifth. The language of music clarifies this type of physics- the belief that musical sounds are embedded in humans—the description of how sound comes from "standing" waves: sound waves into harmonic forms. "The modes" stay fixed, giving us the different tonal/pitches we hear. Simple Harmonic Waves are exact and straightforward but become complicated when added. These can be "decomposed" into simple waves by physicists, engineers and astronomers. The analogy takes a word and "decomposes" it into simple letters of the alphabet. The technique, considered simple, is called "The Fourier" transformation and is used as a fundamental tool in research. So, when used in concert with these two concepts, Fourier and Kepler's notion concerning planets and music contribute to an understanding of the Universe's large-scale structure. A necessary consideration arises: what is the physics that leads to the foundation of galaxies, and what is meant by these considerations; there are approximately billions of galaxies—the common understanding: is cosmic background radiation, 14 billion years of our known Universe. What is measured is a "seething vibrating ocean of plasma-charged material like the sun's surface. Waves existing as tiny little ripples undergo gravitational collapse with dark matter, we don't know what it is, but it's needed to form galaxies." Alexander wants to understand this association through music, all the while contributing to the language of jazz.

The Physics of an Instrument

What makes a musical instrument sound as it is? First, consider the instruments used in this talk, such as the bass and saxophone. Both were demonstrated to vibrate at the frequency of the musical note "A"; however, each sounded uniquely different. Although, when an instrument is processing one note, each point on the x-axis corresponds to one frequency, one vibration, as it were, "as the vibration sweeps across the instrument, it generates a range of vibrations, a spectrum of vibrations at different amplitudes. The one you hear as "A" is the loudest; the others, the brains perceived as the timber of the instrument, the signature, the voice or personality of the musical instrument; this reveals or represents the material or geometry of the musical instrument. We can examine the spectrum using the Fourier Transformation idea, decompose it and determine which musical instrument is being played. The above is the principle behind the synthesizer and is, in fact, Fourier physics in action. What is the reveal from all of this? Fundamentally, it is the idea that all objects vibrate and generate a whole set of vibrations. We can detect different resonances that disclose the geometric balance of the musical instrument. And so, "by approaching the chaotic cosmic micro background radiation, one can decompose the waves of the Universe vibrating similarly, as we did for the instrument. When applied, one sees the Universe functions as a simple musical instrument." The first peak (when grafted) corresponds to the loudest note, "A"; the other peaks represent the geometry and the rest of the materials that make up the Universe. What was this material? Because of the graph peak at A and how the early Universe vibrated, the material makeup could only be dark matter—the contributed work of Canadian Noble Prize-winning physicist Jim Peoples. Coincidently, hydrogen (the most abundant element in the Universe); and concurrently vibrates at a frequency of 440Hz, which identifies as the note A. Stringed instruments collectively tune to A 440Hz, and up until the advent of portable electronic tuning devices, most string musicians carried with them a tuning fork calibrated to A 440Hz, and some probably still do.

The Quantum World According to Donald Harrison

|

| Donald Harrison Jr. (Photo from Treme fan site) |

Harrison (when asked) how he comps a solo, Harrison eventually answered that when he solos, he doesn't play the changes (chord changes) but instead plays outside the changes because it sounds more "hip." Harrison explains that it is similar to Quantum Mechanics; what?! How? He answers: " I don't play in the changes; I play through the changes." After three years, Harrison and Alexander developed "the strategy for jazz improvisation," I lined up with how the scientific community thinks about and interprets Quantum Mechanics. For example, using "Feynman's Path Intergral," a ball thrown in a straight line follows a unique path; no matter how complicated, it's always unique. Likewise, Feynman says that when a quantum particle moves from A to B, a quantum particle has to transverse many possible paths from A to B, some utterly crazy and random in the movement. So, how does one interpret this musically? Alexander says: The Harrison-Alexander Quantum Improvisation Accepted Path for Integral offers a simple explanation as a fundamental formulation of Quantum Mechanics.

In the same way, a quantum particle starts in a given position, a musical note is envisioned as a particle moving across many musical notes/particles to an endpoint. So, analogous to music, there are many notes between the endpoints, and all are valid possibilities when improvising. Improvisation is nothing short of considering a whole set of infinite possibilities going from point A to B. So, when improvising a jazz line, riff, or solo, the musician can consider all options: "playing through the changes." Therefore, the interpretation; quantum particles improvise their way from points A to B. As an amateur jazz musician, this concept was abundantly clear and valuable to my vamping solos.

Application of Ideas: To be Played in Real Time, The Harrison/Alexander Improvisation

- Accept path integral as a fundamental formulation of Quantum Mechanics

- Analogize particle with a note

- Donald Harrison " You don't play the changes...you play through the changes."

- In the moment, there is a wide range of potential possible to consider

- Target the endpoint and play through the changes

The point is that there are many different paths, and it doesn't matter which course takes you there; you start anywhere within changes. The approach you take is where you end; this takes a lot of practice: using this strategy. A musician employing this strategy stops dealing with chord changes V, II, I or dominants, minors or sevenths. Still, instead, they need to internalize the beginning and the end of the chord changes and where they land; this takes practice strategy. In Quantum Mechanics and discussing the macro Universe, one must consult the micro Universe in concert. An essential factor that guides Quantum Mechanics is symmetry, the organization of different nuclear matter states governed by strong interactions; the Nobel Prize was awarded to Murray Gell-Mann (1969) for discovering the underlying eight-fold symmetry SU(3), which fundamentally colours the different nuclear matter states governed by the symmetry principles of the above theory. Alexander states that one of the ideas he has been toying with as a person who tries to use his music to inform his science or use physics to clarify his music, so, recently, he has been studying the use of weird parallels like "Quantum Chromonite," or "the organization, consent tones, or how in tonal space, perfect fifths, fourths, diatonic system are organized."

He explains that there are many musical systems, but most cultures, regardless of their musical identity, will recognize the perfect fifth almost innately; it seems registered in us as humans re: experimental psychology, Carol Krumhansl. Once humans recognize this, we have the structure, and your journey continues.

The Jazz - Live

|

| Joe Handerson's Page One album cover |

Alexander calls Denis Rondeau* (upright bass) to join him on stage and informs the audience that they will perform three tunes together. Joe Henderson's (tenor saxophone) arrangement of Kenny Dorham's Blue Basso from Joe's debut album Page One was the first tune performed. Joe Henderson was a coherent factor in Alexander's life since he was also Alexander's saxophone teacher; I was left dually impressed: unaware of this fact mentioned in passing! Alexander's rendition of Blue Basso did more than pay homage to his once saxophone teacher but; demonstrated mastery of the instrument, exhibiting expressive phrasing, imaginative use of chording and scales while playing around the melody, flawless transitions and some genuinely outstanding riffs. It's enough to listen to the music when attending a live performance, but watching the musician deliver their performance is just as meaningful. Alexander's body language spoke of his total investment in the piece: delightful!

Next, Geroge Gershwin's Summertime. What about this masterpiece that hasn't already been said before (probably better than what I can)? It was enough to close my eyes, be in the moment, and listen.

|

| Denis Rondeau (denisrondeau.com) |

*besides being an upright free-lance bass musician of outstanding musicianship, he is also a humanitarian who has spent the last 33 years teaching music to blind children. So, I doff my hat in your direction, sir.

Coda

Stephon Alexander is truly a unique work of both art and science. His presence encompasses the embodiment of a Renaissance man dipping both feet into many unknowns while trying to formulate an understanding or comprehension of these mysteries. He's not afraid to challenge these percepts, and Friday night, he did so with his heart on his sleeve, and I'm grateful we were there to share a slight sliver of this man's remarkable talents in science and music. I'm thankful for the Perimeter Institute's continued dedication to public events encouraging us to live and learn. I thank the staff, sound, video crew, and volunteers for their generous contribution to an eye and ear-opening evening for many. Alexander's foray into how the notes and numbers share a connection and how they behave in concert at a Quqntum level is an area I'm sure many have never dared contemplate. Can physics and jazz co-exist in the same plane? Conclusively, they can, and Alexander demonstrates the distinct reality of this cohabitation in the house of universal arts and science.

Stephon Alexander's Website

The Jazz of Physics: Stephon Alexander Public Lecture (video)

Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics

BOOKS BY STEPHON ALEXANDER:

Disclosure:

Some of the links may be affiliate links, meaning that we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase at no additional cost to you. We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. However, this does not impact our reviews and comparisons. We try our best to keep things fair and balanced. By purchasing through our links, you are helping us maintain this site.

Comments

Post a Comment