Often enough, there comes into one's life a work of literature so profound, so emotional, so influential that it alters the way you think and perceive the world around you; for me, that book was Goerge Orwell's 1984. I was in my very early twenties when, upon a recommendation, I read said book, and to say sheepishly it changed the way I considered government and its conventions would be an understatement. This book's literary landscape turned my naive, pleasant, bucolic interpretation of what I saw and knew into a countryside poxed with the scars of humanity's barbarities. Insensitivities to the human condition doled out by the ruling totalitarian government known as The Party under the ideology of Ingsoc, its population paid in the currency of fear, subjugation, loathing, and torture; a lifetime of cowering, eyes on the ground, assimilation of the lower classes to feed the vacuous hoards, the principle of obedience. Not the obedience of a child to its parents or a dog to its master but undeniable obedience by the distillation of lost freedoms lost dignity, and most importantly, loss of self. A societal widget whose only function is defined by how the government can compel by denial. Human existence: no more than biological tools used to perpetuate the bureaucratic lies, the privileged few who manipulate and mangle the masses. The most chilling aspect of this is the quote: ''If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – forever.'' When I read this, (this one single) sentence threatened me as a young man; everything I held valuable now seemed to evaporate and be replaced with loathing and contempt. Your face is what you project to the world, the most beneficial aspect of self; it defines your place among the many in the crowds. In slang terms, to ''give someone the boot'' usually infers that you are not wanted anymore, and so, the quote suggests that there is no individuality, nameless and faceless in a dictatorial, totalitarian world; forget the special snowflake, only the grey order of power, control, and oppression. Existence is merely existence for the state to be done as the state wishes. Humanity: reduced to its lowest fraction. Where are the wills, the dreams, the purpose, aspirations? Without these, humanity is fodder for the canons, ready to be broken at the end of a mind-altering electrode. Heaven, please help us.

In this dystopian era, the world is rampant with desperation. Desperation is quite palatable to the reader of both novels. The human mind operates as if stuck in auto-correct: constant self-censorship where any action deemed anti-party will be referenced with consequences: The Ministry of Love re-orientation or possibly medical intervention. Friends and family are encouraged to police its daily operations with constant Party surveillance. Human pitted against human for the good of the elite few with positions of anarchy disguised as a government: Big Brother is watching. Very few options exist for someone living by the seat of their pants in such situations. Humans become government commodities. Historically, humans as enslaved people are commodities; humans in organ trade, paid surrogacy (aka commodification of the womb), and human trafficking are all commodities. Once a commodity, human life lacks respect and is more akin to an article worthy of disposal than accretion.

Totalitarianism: one of man's most insidious products of concept, division, and dehumanizing political intervention whose institution is designed to control every aspect of human life, from the mundane daily aspects to the very elements of privacy gained by coercion and repression. It demands complete control of association and assembly and the right to free speech. Its power extends beyond what people think and believe: all mysterious, elusive, omnipresent, powerful, unmerciful political deity that demands complete capitulation: unquestionable obedience and corruption of self-preservation. A bleak existence for its populace. A continuous form of propaganda that usually bears radical changes in its people's history, bred to instill fear and unfathomable loyalty in its citizens. A one-party government generally metes out the assertion of control. Objection usually results in undesirable consequences. Slogans peppered in irony play as a constant reminder of what is expected of its citizenry. The reshaping of language also becomes a contributor, a weapon of control. Propagandist language employs various techniques to extract loyalty further; simple inversions of everyday phrases and oxymorons are used to confuse, redirect, and submit. Totalitarianism is a greedy god; its hunger is insatiable, an appetite never satisfied with what it has gained; it greeds for more. In today's modern world (at the time this essay was written), the closest we come to this scenario is the emergent country of North Korea. As mentioned earlier, it is not dystopian but totalitarian.

Both novels, 1984 and Julia, exemplify these nightmarish conditions.

As a young man reading 1984, I often pondered about Julia's character: her personality, her likes, dislikes, dreams, and all the attributes that contribute to human hope, planning, growth, development, and wellbeing: a well-grounded woman. Julia is Winston's love interest and seems to share the same hate for the Party; she forges the same level of rebellion and disobedience. Winston, however, has some lofty considerations to grapple with regarding truth. As humans, truth is a condition, an ideal worthy of the compulsive drive that compels us to question the barrage of incoming information that presents itself for our inspection and classification in a form that is desirable enough to become acceptable. Winston's truth comes prefabricated directly from the Party; he is compelled to believe this no matter how hard he tries to resist. It is abundantly clear that truth is what Winston craves the most; it is held in the highest esteem and drives his eventual inevitability. Why is Winston's devotion to truth constrained with a pinpoint compulsion so that he is entirely focused on its obstinacy? His dedication to the truth equals that of a Pilgrim tracing the arduous Camino de Santiago; he must challenge it. Winston is at odds with the distortion of truth as offered by the Ministry of Truth; his conflict stems from the fact that his essence in this society is to create abominations concealed as truth for The Party dogma: his conscience instills in him a struggle whereby his daily occupation contributes to a distillation of fabricated events foddered to the public as truth. His job is to lie for The Party's shortcomings, so he rewrites history that he knows indulges The Party's failures. The Party aims to create a society where everyone is accustomed to digesting the lies as everyday common events and knowledge without circumspect: urban sheep, people devoid of intelligent thought and the discipline of forward thinking. But some people like Winston believe in themselves and resent the omnipresence of government. Though Winston is unfamiliar with democracy, he craves what it represents through what he does, sees, and logically deduces his inherent right as a free human being. What he is forced to endure is inherently wrong. He believes in freedom of freedom, the right to speech and thought without repercussions and government malice. Winston is fearful that the Party will whittle truth into oblivion. Every fibre of his wellbeing believes the Party's corrosiveness will divorce the populace from the truth. He feels stripped of his humanity and craves control. Julia, on the other hand, contrasts Winston.

The use of language, or rather the manipulation of language, is exemplified in both novels as a means to exert power and control over the population. Newspeak (the official language of Oceania) is, in fact, a powerful manipulative tool that ushers in both control of mind and thought. If a population can adapt to a newly formulated form of control through language, they can adjust to any level of machinations: the contortion of lies as truth. Pounding away at minds made more pliable through the continuous recitation of state propaganda can easily have people salivating like Pavlovian dogs eager to comply in the absence of reward. You are alive; is that not a reward in itself?! The corruption of thought and language are corruptable bedfellows; mutual corruption gives birth to Newspeak. Newspeak's contribution to this totalitarian society is not to enhance or enrich ideas and concepts but to distract, detract and dismantle these virtues. It's more challenging to create when you have a vocabulary of only three hundred words, many of which need more exact definitions and substance in their ability to express more complex, concrete thoughts as constrictive or as in criticism. The lack of complex language skills leaves a population hostage to the most basic intuition. Elimination of words by omission or penalty of use can cripple a society. The adage: You can't miss what you never had can also apply to words. For example, the idea of liberty: if the word is removed from the lexicon, the concept can not exist, distorting reality, and the notion will not be missed, a plus for a mistrustful, jaundiced government. The elimination of words stifles growth and expression; it atrophies the mind. Once reduced to a state of de-escalation, the mind dwindles generously, allowing the government to manipulate its citizenry; the state embraces the destruction of family and church. Most people find that the truth can be an insufferable burden. The backdrop of totalitarianism, the crux of its existence, ensures that the populace is constantly supplied with their version of the truth. Thus, they are confident in the assurance of what they believe to be the truth. It's so much easier when the government assumes the role of Big Brother. Isn't it? Big Brother's restrictive chokehold is evident in both 1984 and Julia.

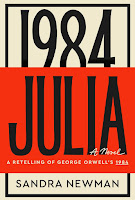

Sandra Newman, the author of Julia, was approached by the George Orwell estate and commissioned a literary work focusing on this dystopian's other central character and Winston's romantic partner, ''lovers in a dangerous time'': the neglected, little-known heroine Julia, capturing and remaining faithful to the original 1949 dystopian novel. We first learn about Julia; she has a surname, Worthing (somewhat suggestive); this always caused me concern: she had no surname, making her incidental, a nobody and guileless, and she is not. Julia's character becomes incredibly intimate with Winston. We are privileged to his surname but not hers. Newman remedies that and graces her with an identity. Something as simple as a surname validates her complex nature in the narrative. The text bears remarkable similarities; that is to say, both are written to exemplify the bleak, hopeless daily struggles forced upon society when compared to sheep. Newman's courageous foray into this remarkable challenge rewards the reader with unbridled ambition. The only valid comparison rests in the fact that both novels capture the essence of the time. Literary style and slackened censorship restrictions have created what, at times, presents to the reader a more raw account that stretches beyond that which Orwell at the time could not. Still, both novels complement each other, and though ( at the time of publication) 75 years separated the two, it's to be understood that the events are occurring concurrently; both novels become intertwined. Both characters have occupations within their daily grind; both function to operate in a world that offers a different slant on accountability. Julia is anchored in the cold, hard work of technical machine maintenance. A job that includes a risk factor while Winston's trade is rewriting history. Based on their occupations, there is a role reversal from the onset. The more dangerous job that traditionally would be delegated to the male is awarded to Julia; the softer job goes to Winston. This tells us two things: one, human tenure in this life is not determined by gender, and two, their occupations cause them to approach how they think and perceive an alternate perspective. Orwell's take on the female role is in favour of misogyny, and it is to be expected based simply on how females were viewed historically. Newman need not adhere to this presentation of the female and makes Julia a more substantial, more forward-thinking individual (her job in itself prepares us for that); Julia's constitution is not that of a thin gruel; instead, her strength of character and sexual gratification have encouraged her to engage in ''sexcrimes,'' which eventually including Winston.

Julia's role in this wilted Dystopia is as a mechanic responsible for maintaining what probably amounts to overused, old, mainly worn-out mechanical devices forcibly employed to work on ''Fiction Machines'':''I fix whatever brakes, comrade.'' The irony is not lost; Newman presents our heroine protagonist with the herculean task of ''fixing'' social morays and feminism ( presented as a reoccurring theme). What makes Julia suitable for this task is that she is not Oceanian by birth. Her origins stem from SAZ (Semi-Autonomous Zone). As an outsider, she must develop survival coping skills combined with her knowledge of SAZ to make her more formidable for the task at hand, her Achilles heel: ''sex crimes''; taking us to places in this novel that Orwell could not base on the narrative: Julia's existence in 1984 is a means to further Winston's obscene interpretation of the female role in war-torn Oceania. Julia has an enormous appetite for sex; her history reveals her predilection for the carnal arts. Newman uses this symbolically as a badge of female empowerment, like the badge Julia later wears to announce she is pregnant within the Artsem programme. However, the essence of intimacy is abundantly clear in her relationship with other women, as illustrated in her interactions with her rooming companions; but, as with any relationship, complexities are the motions that give rise to the notion that even within your gender, extreme possibilities can exist. Stripped and laid bare, this government diplomacy of hate dominated by male interests still focuses on women as vessels; I am reminded of Margret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale.

Newman's Julia's character far exceeds that of Orwell's Winston. She has a complicated nature; she is resilient and exhibits the cryptic colouration of a social chameleon. She is quick to assess any situation. Her early childhood bears witness to the loss of her father, executed for Intransigence, where Julia's attendance is compulsory, which, in turn, only hardens the husk. Her finesse lies in the relentless attraction to sex, all the while skirting the Party's attempts at being caught. On the other hand, Winston lives by the moment, accumulating hate for the Party. He never looks at the sex he enjoys as anything but temporary, never giving in to the notion of love or longevity. I think the meaning of sex confuses Winston. Winston's aggressive anti-party rants substitute for sexual foreplay, and his post-coital Party rants act as his pillow talk. The only commonality they share is in being caught. Julia uses her sex as a weapon, thumbing her nose against the Party; Winston uses sex to momentarily forget the hate for the Party, only for the hate to re-surface, reformulate and re-born itself as an even more profound, concentrated hate than before the sex as if sex is his stimulus to hate the Party. Winston's aggressive anti-party rants act as his sexual foreplay, and his post-coital Party rants act as his pillow talk. They are opposed; their personalities grate and chafe at their metaphorical skin. The Party has taught Julia how to be resourceful, crafty and design; it has taught Winston reserved bravado and grins laced with fear. Two people who present themselves as obverse and reverse in a world that has compressed them into counterfeits of man and woman. Newman's version allows the reader to see rays, glimpses of hope and change, while Orwell's remains staid and institutional.

Having considered both novels and the approach to the relationship between Julia and Winston, I could not help but conclude that Julia is Winston's foil in 1984, and the reverse is true of Julia. Everything Newman has achieved in creating Julia, even in her moments of wavering, allows a complicated character to appear unsophisticated but does not detract from her underlying objective of self-severing. Winston's (as a foil) dreams are significant, earth-shaking, culminating in total government collapse; Julia's lacks the grandiose overture of Winston's view; her's is locked in the observable and is more akin to a quiet riot. Julia's opposites are essential to demonstrate who has cunning, survival coping skills while the other does not, possibly laying bare the foreshadowing of who mentally survives the Ministry of Love and then the irony of betrayal. The tiny cement that made them human.

It is impossible to read these two novels and not be cognisant of the potent underlying theme of human sexuality and its role in politics and humanity. In this dystopian world, all the rules concerning the appropriateness of sex are corrupt. How often have we heard that the government has no business in the nation's bedrooms? However, you would have to believe the opposite in these two novels. The Party, like all else, has a monopoly, including the ideology of sex. Big Brother condones sex for procreation among married couples (preferably reserved for Party members and only if approved ) to add to the expansion of the Party membership. Children who will become future leaders and remain highly motivated to tow the Party line are conceived artificially and reared by mind-altering Party institutions. Women are political vesicles for the proletariat to strengthen the masses for military might being fodder for war; Oceania needs bodies since it is always at war. Party impetus of this plan: encouraging the proletariat to read cheap pornographic novels; quickly done since the proletariat is universally considered as expendable and regards sex as a distraction. Julia worked on producing such reading material at some point in her life. Sex for recreation is heavily frowned upon: penalty of insurgence; the Party's objective is to disengage all pleasure from the sexual act and replace it with unquestionable love for the Party; sexual pleasure competes for Party loyalty and is no substitute for the joy that they would be extracting from the intoxication of worshipping the leader.

We now must focus on the most frightening aspect of both novels: Room 101, supplied to the downtrodden public by the institution with the oxymoron monitor, The Ministry of Love. The only element of love in this title must have come from the person who created the incongruousness in its meaning—maybe even from O'Brien himself?! It stands to reason that before the ministry adopted such a misleading name, citizens may have had a different concept of what this meant and that it promoted love; only through time and experience did they learn that its main currency was hate and fear. Citizens of questionable sedition or wayward thinking receive rewards of long hours or days of brainwashing and tortured submission, and as in Winston's case, frontal lobotomy: the ultimate quest in catatonic submission. Only with time did the reputation of its existence precede itself. What better way to enforce obedience (at a minimal cost) than through word of mouth? Fear at the cost of one's life has a forward way of repressing one's rebellious streak. The philosophy of fear and its innateness is the staple ingredient used to exercise Party power and omniscient reach. The Party has an academic, encyclopedic understanding of how fear and terror vary from person to person. Based on comprehension, it's easy for the Party to crush the will and spirit preying on the victim's deepest nightmares: evil has no bounds. For Winston, fear comes in the form of rats; for Julia, rape and loss. It is apparent that no one is immune from the ''love'' administered by this ministry; even the enforcers can one day be equally subjected to its loving embrace. Party status is not a get-out-jail-free pass when chosen for ''re-orientation.'' Death while in the ''loving hands'' of the ministry is avoided at costs for the simple reason that if death in room 101 were wholesale, then the Party would, in effect nullify its ownership to absolute power and the fear of creating a martyr is counterintuitive: together with the notion that you can only kill a person once, but the threat of re-orientation is forever, again the unique understanding of fear.

Julia's account of her time spent at the hands of (Bill) O'Brien is a variant of Winston's: the place is the same, but the circumstances vary; after all, we all know that no two fingerprints are the same, and neither are two means of torture. Julia is subjected to so much torture that she begins to incorporate her schematic torture while dreaming." She no longer existed as anything but shit and pain." All torture eventually results in electric shock, enough that she experiences an out-of-body state. Even while the body is attempting to recover from the insult it has just endured, in the semi-conscious state of sleep, Big Brother Party has achieved the ultimate torture - the mind, and it is capable of inventing torture that the tortures haven't even thought of yet! " Julia shuffled off to an alternate room in the same cot she had been a resident of for some duration. The indignity continues while her urine dries and crystallizes on her skin. To further the moment, once placed in front of a telescreen, she is made to watch a man whom she recognized from her more intimate liaisons when they thought their sex and conspirator ideologies were the fabric of their existence. Torture and starvation change the facial features of a face she once instantly recognized into a fragment of what it represented.

Wintson denounces Julia once confronted with his personally tailored torture machine: a cage housing starved villainous rats made for gnawing on Winston's face at O'Brien's will. A test of fidelity immediately failed by our saint of self-preservation; ''Do it to Julia,'' he announces as his jailor complies with his request. The confrontation of rat versus woman comes at a cost for Julia: brow and tongue become facial fodder for the rat. However, Julia (unlike Winston) has no fear of rats, and with her innate ability for quick thinking, she entices her rat tormentor into her mouth and is formally dispatched. Brave girl, she can defend herself with just her mouth and teeth while her head is caged and restrained; remarkable resilience! The second rat in the cage escapes after removing the cage; the metaphor is not lost. Failing grades for O'Brien (our maven of torture) for being unable to discern the subjectiveness of fear. Winston, although set before a telescreen so as to face the concluding events of Julia's ordeal, has not been watching. Housed in restraints and slack-jawed, he remains asleep, the gravitas of the moment forever lost.

Upon her release and return to The Ministry of Truth, Julia is regulated to the mundane with the title of The Facilities Consultant, which holds no agency. She is sequestered in a tiny room with a governed telescreen and her thoughts. After her child is born, will she be shot or hanged; she resolves to be a good ''Unperson.''

Julia assesses her time (spent) in the loving embracing of Big Brother and Winston's footage on the telescreen. After the abuse that she has incurred at the Ministry of Love delivered by O'Brien, she concludes she hates Big Brother. Her hatred for O'Brien, Gerber, Weeks and Martin makes her feel cleansed. She reflects on what her friend Vicky said about joining the rebels and sees that she was right. Still pregnant, escaping authority, she thinks that for the first time in her life, she is listening to herself and doing what feels is right: ''She went on board, pleasantly aware of her tired legs and the exalted feeling of her own life, of her mind, coursing free and unimpeded.'' Her new resolve takes her to the Crystal Palace; she meets the resistance, the rebel's assurance of safety: '' Welcome to free England, Miss Worthing. You will be safe with us.'' assured by a rebel guard. Her tour of the Crystal Palace (residential usurpation by the resistance) introduces her to the lavishness once catered to Humphery Pease, the incarnation of Big Brother. Julia's tour also includes a brief history of Humphrey Peases and his rise to power. She finds a man who is a shadow of his former self and vision, old, senile, and decrepit; he is as she was at the Ministry of Love: bound, shamed, confused, and incontinent. She had dreamed of the injurious injustices, the horrors she would ply to his flesh once she met him, but upon this vision of Humphery, her compassion as a human shone through all the muck and mire of her course existence as a resident of Oceania. Retribution to the face of her grief and suffering was no reward as to what presented itself to her at the moment. Exacting the equivalence in kind to a slobbering, feeble, frail-minded architect of social misery would have been comparable to wishing such punishment on an unsuspecting child. Forceful, debilitating, dangerous pain on an individual unable to fathom the why of such an action is indeed a shallow victory; he is undeserving of her compassion, unaware he is being gifted such an emotion and is still the recipient of such an exalted level of humanity. Humphrey, as his surname suggests (pease old English spelling of pea), has been reduced to a pea-like vegetative state. Also, Pease refers to his historical past from whence he came: old traditions; a slight variation in pronunciation could easily make it sound like peace (the antithesis of Humphrey's regime). There is an intimation that Humpty (Dumpty) from the childhood thyme could be substituted for Humphrey: ''All the king's horses and all the king's men couldn't put Humphrey (Humpty Dumpty) back together again.'' This suggestive poem is a solid reference for Humphrey's collapse and his failed, intolerant empire; this is Newman's brilliant play of words. Included in Julia's tour is the compound housing political prisoners; this description of prisoners of war is eerily similar to the historical account of Hitler's last stand using children and older men to defend Berlin. During Julia's indoctrination, she is asked to submit to a series of questions to evaluate her further into the resistance and to essay her loyalty and commitment. To her shock, she realizes that these questions were the same as what O'Brien asked of her and Winston when he was pretending to recruit them into the Brotherhood. Was the trapping of the resistance, the uniforms, the force, the question, the decadence any better than what they were disposing of? Was this replacement any guarantee of real change or fundamental freedoms? She feels as detached now as she did when she had the out-of-body experience at the Ministry of Love. In the end, she agrees to the terms,'' Yes'', said Julia. ''Yes, Yes, I will. Yes.'' But will she? Her inner thoughts reveal: ''She didn't have the freedom to think of what was right. She must do what was safe. It was as Appleforth had said: one had no choice, one must only live through it has if one had.''

Sandra Newman's book cover states it is a ''retelling of George Orwell's story 1984''. Newman's novel is a brave and powerful adjunct to a story that already breeds a sense of finality, lack of hope, and despair. Her version is good and does not disappoint. Newman builds a strong female character who goes the full measure; she is an intelligent, sexual woman who knows when to use her wiles in a society where one's wits count as currency. A close introspective of Julia helps to define better who Wintson was from the point of view of his love interest in a cloistered, suffocated, dehumanizing, loveless regime. Their existence with each other, like their countryside affairs (for a short time), produces a bright, sunny, ephemeral repose from the gray grind of subpar life. Their relationship exemplifies the differences that help propel the story forward. Newman masters the tense, apprehensive moments Julia endures in the name of self-preservation; she follows the more petite, minor rules while challenging the ones with more consequential outcomes. Julia is edgy, soft, challenging, and compassionate; what a perfect balance! The novel 1984 needed a novel like Julia if for anything but to illustrate that the suffering was just as complex or even more complicated for women. Winston never has the same choices as Julia, and in doing so, the contrast blooms. Julia could be read as a stand-alone, but it reads better when 1984 is read or re-read.

"It was rather as O'Brien had said: 'We shall squeeze you empty, and then we shall fill you with ourselves.'"

Recommended reading: 1984 and Burma Sahib

|

| Click to Purchase |

|

| Click to Purchase |

|

| Click to Purchase |

Disclosure:

Some of the links are affiliate links, meaning, at no additional cost to you, we will earn a small commission if you click through and make a purchase. We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. However, this does not impact our reviews and comparisons. We try our best to keep things fair and balanced.

By purchasing through our links, you are helping us maintain this site.

Comments

Post a Comment